The Boat to Timbuktu (1 of 2)

In 1990 I spent four months living in Niamey, Niger, a dry poor inland country in the center of West Africa. My sister was writing her dissertation on international agricultural economics, and I was taking a year off from college. During that period, I worked (sort of) as her research assistant.

At that time, very few people went to West Africa. The was no tourist trade of which to speak, and the expatriate community of Niamey consisted of Peace Corps volunteers, U.S. embassy staff, and employees of the U.S.A.I.D. The population was so small that between the three, two softball teams were assembled to play once a week at the U.S. embassy grounds, and Peace Corps volunteers had basically an open pass to use the ambassador’s pool.

I was seen as Peace Corps ‘lite’ among the community as my work wasn’t much different than theirs, nor as demanding. I would take supplies to research teams, measure and map fields, and, most importantly, keep my sister from being a workaholic. Through all this, I met two volunteers named Styke and Dave. In October, they were planning a trip to Burkina Faso and Mali. The highlight of there trip would be take the river boat on the Niger River from Mopti to Gao and to visit the fabled city of Timbuktu. How could I refuse?

On October 11th, we set out on a three-week journey that would take us by bus from Niamey to the capital of Burkina Faso, Ouagadougou (best city name ever), and then by train down to Bobo-Dioulasso, the second city in Burkina (and second best city name ever). From there, we would catch a ‘bush taxi’ to Mopti in Mali and stay at the Peace Corps hostel. Next would be a five-day trip to Dogon country to hike among the cliffside villages, which had only been recently abandoned, before returning to catch the Riverboat to Timbuktu and Gao.

Ouaga turned out to be a loud, vibrant city but without much to offer. A young and growing city, it had little for the visitor. Bobo was much more laid back. It had pretensions of being a tourist city, and, being the furthest south I ever got in West Africa, the greenest place I saw, far from the Sahel (the arid region south of the Sahara). We rented mopeds one day and made our way to a forest stream where, against our better judgment, we swam under the jungle, watching monkeys in the trees and along the riverbank. When at last we left, we were glad to go as being three of the few tourists, the Bobo mafia seemed to know our every move, and we were hounded everywhere we went.

Swimming in the Laginette near Bobo-Dioulasso

The next leg of the trip was to get to Mali by bush taxi. Ahh, what is a bush taxi? It was the most common form of public transport in West Africa at the time. Private vehicles moving from ‘bus’ station to ‘bus’ station, cheaply carrying the bulk of people and goods in the region. They were almost universally Peugeot 205 station wagons (neuf places, or nine seats in French) or Toyota minivans (dix-suit places / eighteen seats). Often poorly maintained, they never appeared to have preventative work performed, and there is no limit on carry-on bags. I never saw one where the wheels had all the lug nuts.

We showed up at the dusty station (gara) at the crack of dawn to catch the first neuf place heading to Mopti. The cars wait until full before they depart, and we didn’t leave until well after noon. I appeared to have developed a light case of the runs and got to know all four stalls of the public restrooms, little more than squat and drops (two boards over a shallow hole), all too well as we waited.

There were six people and many bags and chickens on their laps when we left. The drive was relatively uneventful (or at least I didn’t write about it my journal) until we reached the border crossing with Mali. Poverty and corruption tend to go hand in hand. When government officials cannot make an adequate living but are given a modicum of power, it is not a surprise that they use that leverage to take care of their own. Not saying it is acceptable, but it is understandable. It was getting near dusk when we pulled up to the gate at a square concrete building. An armed guard came out and took everyone’s passports, and walked back into the building. The border was due to close in about twenty minutes.

After ten minutes, they called the passengers in one at a time, and I was first to go. Not speaking French or any local languages, I was quickly dismissed (without my passport). Each of the African passengers was taken one at a time, and each came out with their respective documents but visibly upset. At last, they called me back with Stryk and Dave together, clearly not wanting any linguistic difficulties.

The interior of the building was a simple box bisected by a concrete wall with a glazed window, slot, and ledge. The man on the other side spoke in French to us, and Stryke replied on our behalf. The following is my transcription from my journal dated the 17th of October.

“I know you paid for your visas in Niamey, but there are things you have to pay to cross the border.”

“I don’t understand.”

“You don’t understand?”

“Well, a little.”

“Oh.”

There was an uncomfortable pause.

“We are Peace Corps volunteers like you have here in Mali. We don’t get much money. We are not rich tourists, we on vacation from Niger, where we work. We are visiting the Peace Corps in Mopti.”

“Pay what Peace Corps will pay,” and he slid a cassette box under the window.

The three of us conferred for a moment, and Stryk put a 2,000 West African Franc note in the box, roughly $8.

He took the box back, and there was a long, uncomfortable pause again as he turned and began typing on something. We just stood there.

Finally, he grabbed our passports.

“If that is what Peace Corp will pay, that is what Peace Corp will pay,” he said as he slipped the passports back under the window.

We quickly went out to the waiting bush taxi, where the other passengers were still fuming but also worried that they were about to spend the night on the ground. Relieved to get into the car before the border closed, we headed off. We reached Mopti late at night.

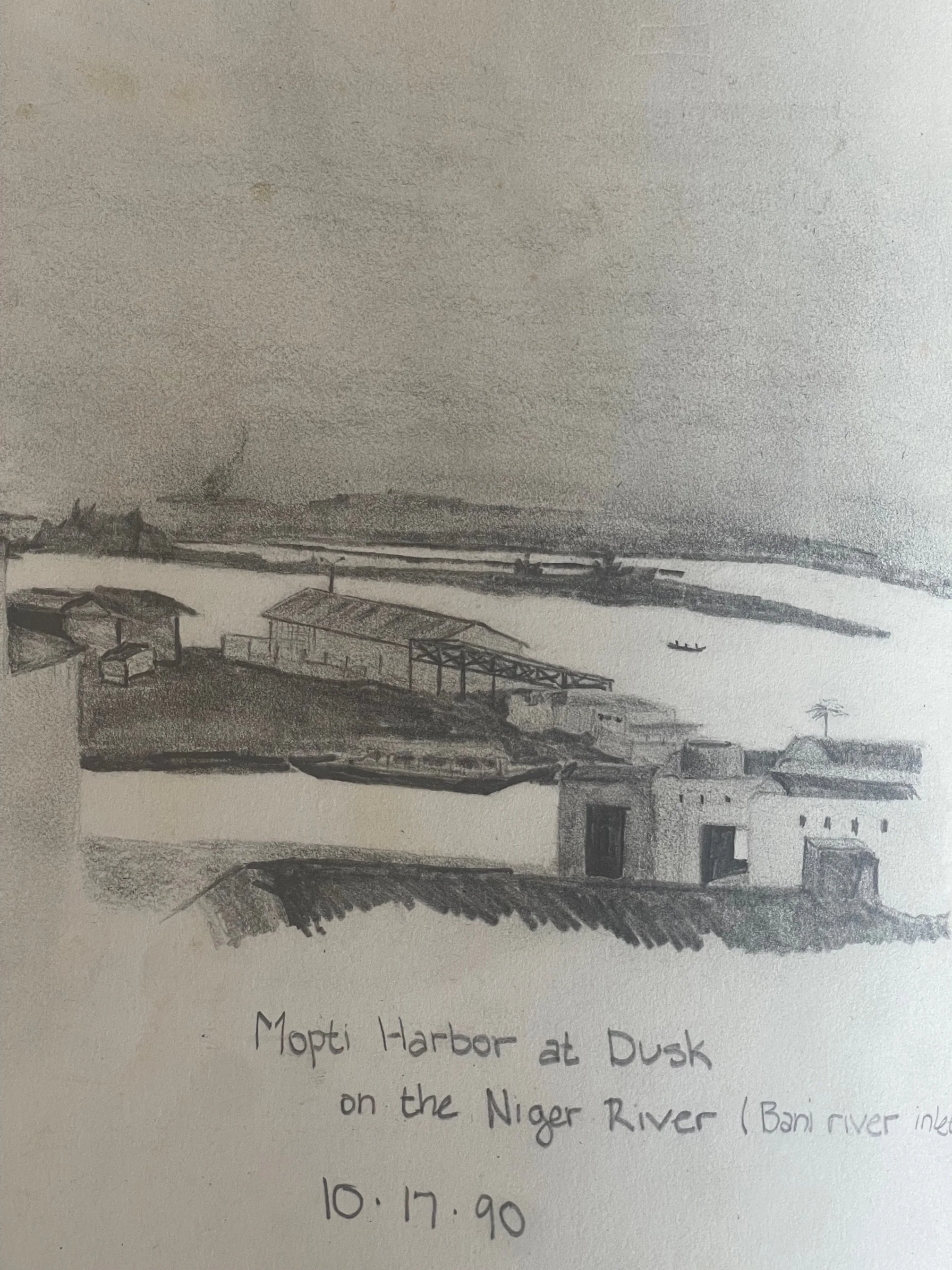

Sketch of the Mopti Harbor from the roof of the Peace Corp Hostel

Exhausted, we spent the following day relaxing at the hostel, and I took to the roof to sketch the view. We spent that day planning our trip to Dogon country, finding a guide, and recovering from the day before.

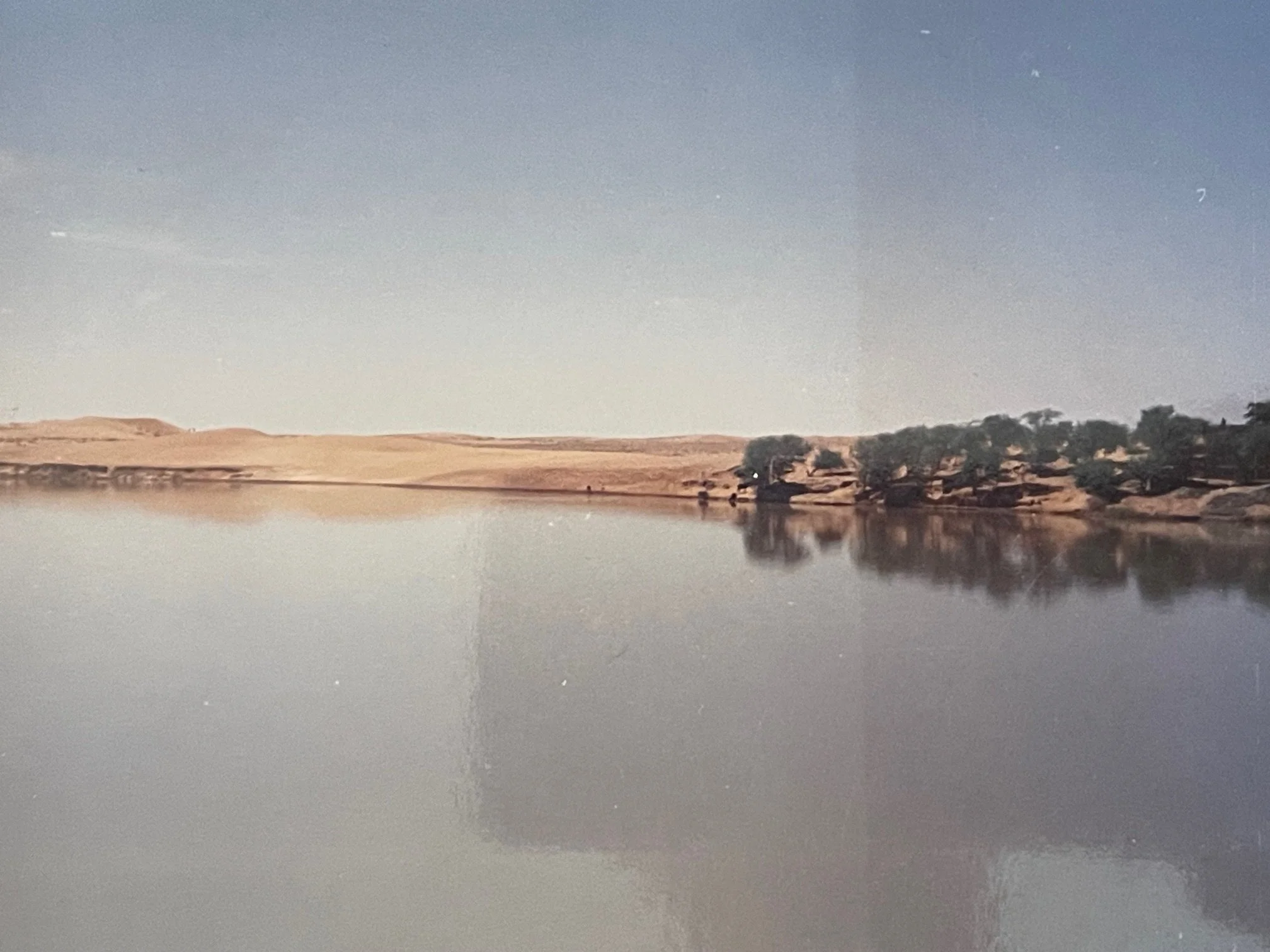

The Dogon people and the Dogon region lie between Mopti and Burkina Faso along a two-hundred-mile-long escarpment. This long cliff, marking the edge of the escarpment and the plains, has been the home region for these people for more than 500 years. Much like the Native Americans in the southwest United States, they built villages in the cliff face for defense and farmed millet and sorghum at the base. It was only in the mid-nineteenth century that the Dogon people moved down to new villages in the plain or up onto the escarpment, abandoning the cliff villages of their parents. To visit these towns while they were still a part of living history was to travel into history itself. We didn’t realize just how much history we would get.

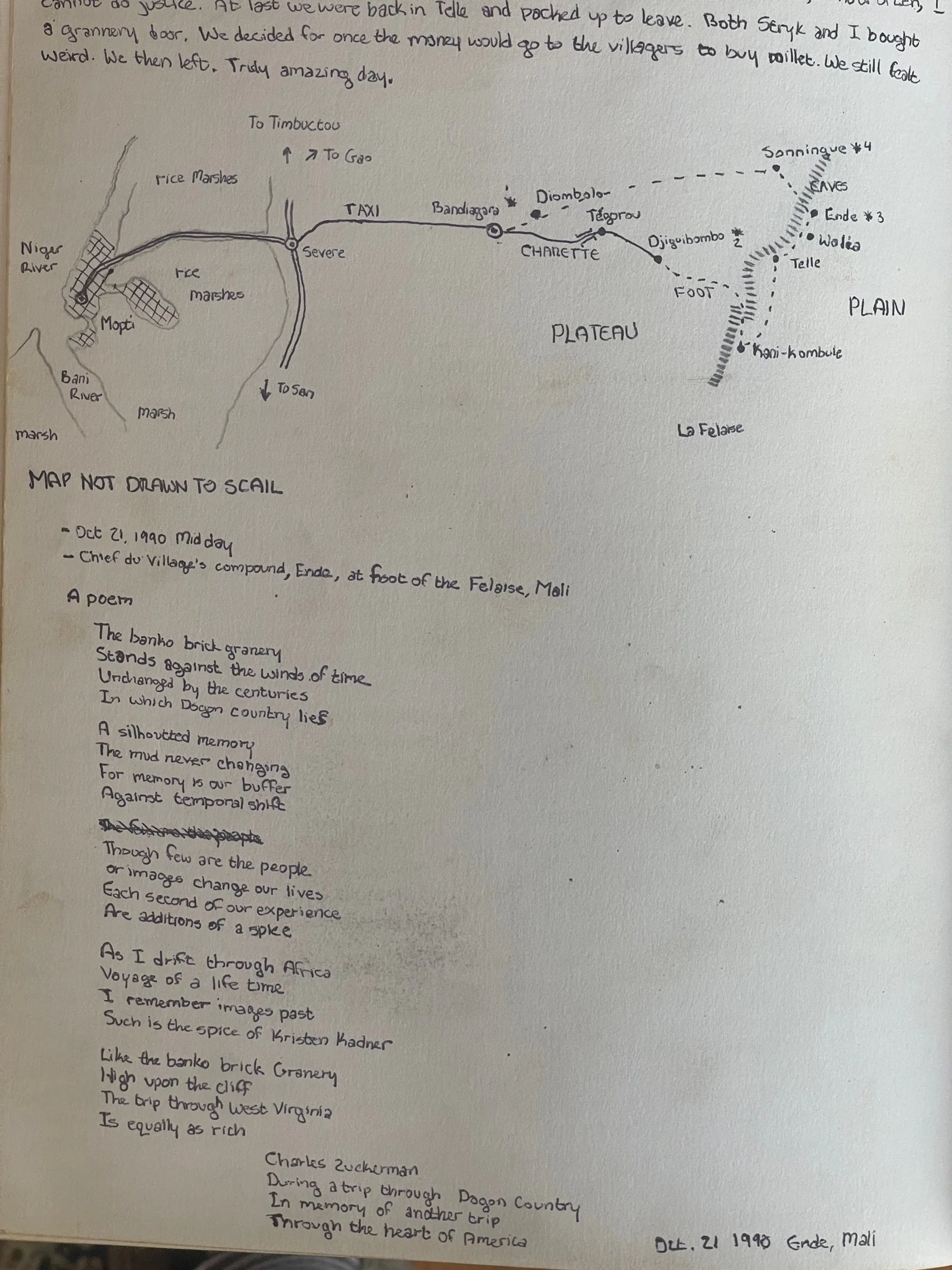

Our route through Dogon Country from my journal

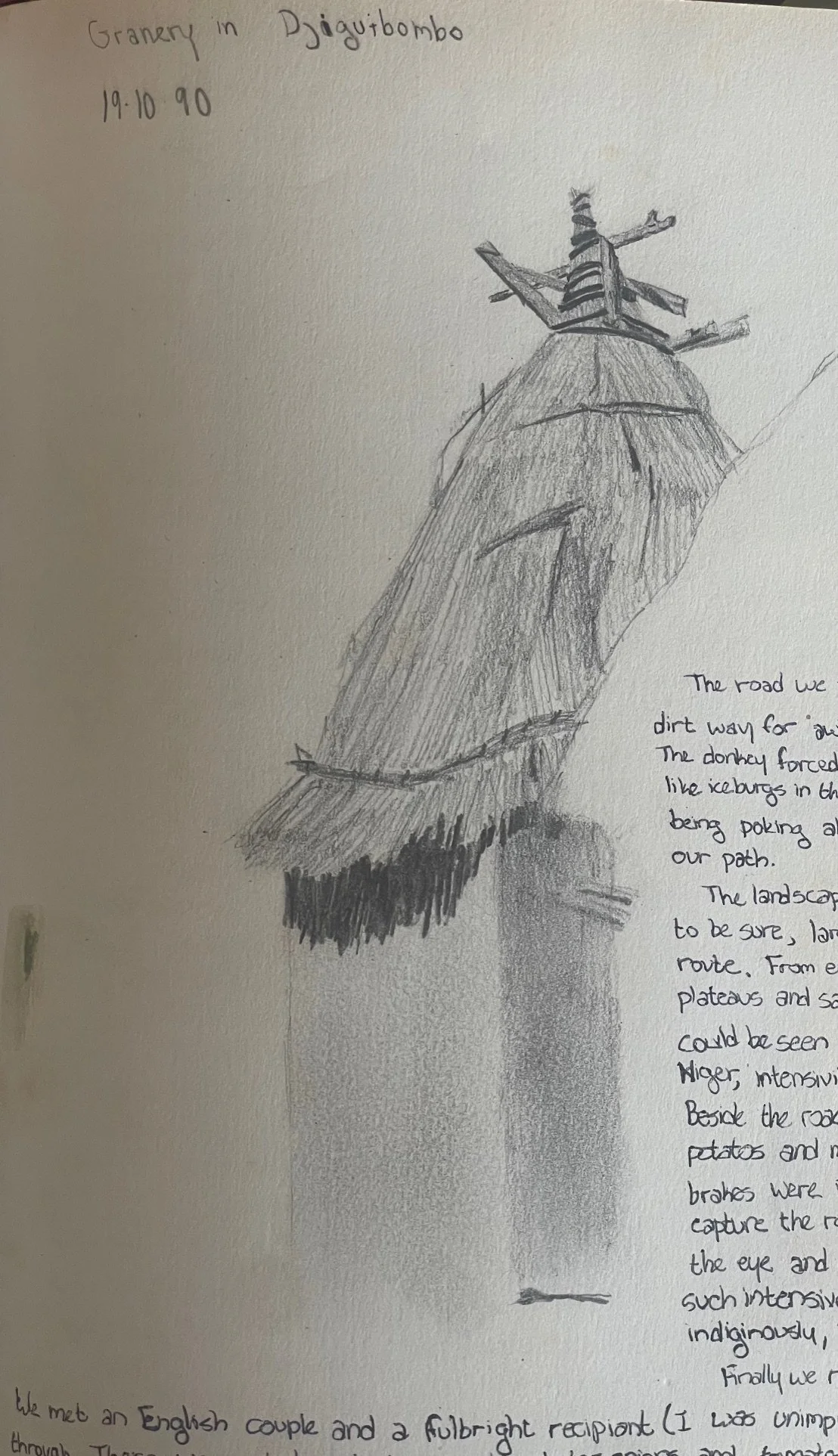

We took a taxi to Bandiagara, the de facto capital of Dogon, before taking a donkey-pulled cart to Djiguibombo, where we spent our first night. Dogon towns are like little puzzles or nesting dolls. The juxtaposition of walled compounds creates a rabbit warren of alleys of smooth brown clay. Behind the wall are several buildings and open spaces creating a maze within the maze of granaries, tiny barns, cooking areas, and mud chambers. Our guide, Mystique, weaved in the history and cultural background of his people, who fled here in the 12th century from further north. Each town possessed two co-leaders, one sacred and the other profane. The latter was responsible for the day-to-day running of the village, while the spiritual leader placated the ancestors and looked out for the religious well-being of their people.

A Dogon granary in Djiguibombo

I awoke under a field of stars. We slept atop the chief’s compound under the Milky Way after consuming local millet beer. The ribbon of milky white stars had rotated in the sky as I waited for dawn to creep over the brown landscape. Once it was light enough, we headed out towards the escarpment and down the cliffs.

Mystique led us down a canyon with a stream feeding lush irrigated fields of millet, potatoes, and watermelon. We came out of the dryer bottom and started heading northeast along the base of the rock face. Eventually, we came to Kane-Kombule, a small dual village, with everyone living in the newer mud enclave on the plain below the cliff, with the abandoned sister village of mud huts halfway up the cliff, accessed by a series of wooden ladders and tiny paths. The residents of this town didn’t descend until the last round of droughts. We continued along to the next town, Telle, where we slept in the chief’s compound and prepared to go up to the abandoned huts above. My final thought that day: “Here I am writing and looking into the beautiful cliffs at a culture with one foot in the past and unsure of where to put their other foot.”

The next day’s entry

“October 21, 1990:

Mystique lead us up. The steep climb passed ancient terraces still cultivated with tobacco and other plants. We first came to the old banko granaries, some still in use. The whole village was abandoned twenty years ago and quickly degenerated. Today the village appears somewhat like ruins, the thin alleys strewn with rubble, holes in the path of banko leading into the empty caverns of the small rooms below… but more importantly the village spiritual chief lives here alone among the ghosts. He administers the sacrifices, preys for rain, and watches the dead who still to this day are hoisted even higher on the cliffs for their final sleep.

[We met the chief who], according to our guide was 99 years old. We climbed the ladder fashioned out of a log into his crumbling hut. The old man pulled himself up from his decrepit bed and shook our hands. His skin clung to his ribs. Here was a man who, in his youth, grew up in the cliffs before the arrival of white man [in Dogon country]. He was here before the modern conception of nation state and even colonial jurisdiction. Now he lives along in the cliffs looking down over the valley. The land is probably the same but now it is called Mali and police, soldiers, tourists, scholars, ex-pats and peace corp volunteers make journeys to his home.”

We spent some time talking with him. He remembered when the first French soldiers came to his village. He remembered the first car that made its way out to La Falaise. He did not lament every change. He felt flip-flops and bicycles were good, but he had no interest in cars. He claimed to remember when Mali became an official colony and when it declared independence. And now he was alone with the past, looking down at the bicycles and the younger secular chief riding around on his Motobecane moped.

We continued our climb through the old village. We came to the ritual house, where he performed his rites. It was painted black for the ancestors and had the red of the blood of sacrificial animals. The hearth was whitewashed for the living. Still higher were more small abandoned holes in the cliff face, which we learned were dug by the Telem to bury their people before the Dogon moved into the region.

We made our way back down to the town of the living and then along to the village of Ende, where we slept before visiting some more caves, climbing the cliff one last time, and then headed back to Mopti for our trip to Timbuktu.

-END PART ONE-

This was originally published on Substack March 28, 2024